4 Questions On NAD/NADH Testing Answered

Unlocking the Secrets of Cellular Energy

5 min read

![]() Dr. Andrea Gruszecki, ND

:

June 10, 2021 at 10:25 AM

Dr. Andrea Gruszecki, ND

:

June 10, 2021 at 10:25 AM

The scientific community is finally documenting what Naturopathic physicians and functional medicine practitioners have known for years: there are three different ways that wheat and wheat proteins can affect the human body. Celiac disease, wheat allergy, and non-Celiac gluten sensitivity all require different treatments and different types of testing for diagnosis.

An individual may be genetically predisposed to Celiac disease, via both HLA-DQ2/DQ8 and non-HLA genes, which results in an autoimmune disorder that damages the small intestine. Risk of Celiac activation is increased with the presence of gut microbiome disruption and viral pathogen exposures. Individuals with Celiac disease often suffer silently for years and are usually diagnosed later in life. The intestinal damage that occurs in Celiacs during gluten exposure can take months or years to heal and can result in severe nutritional deficiencies if untreated. Celiac autoimmunity should be suspected in any patient with signs and symptoms of malabsorption or chronic malnutrition, such as iron or B12 deficiency.

An individual can be IgE-allergic to wheat or gluten and have a classic type I hypersensitivity reaction to ingestion. Allergic responses to foods can be systemic, but often affect the digestive tract and can result in inflammation, diarrhea or constipation, in addition to more classic IgE symptoms.

Lastly, an individual can suffer from non-Celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) which can result in a variety of systemic reactions to gluten, gliadin, or other wheat proteins. NCGS does not have a strong genetic association and has not been associated with the same nutritional deficiencies, intestinal tissue damage, and autoimmune reactions as Celiac disease. NCGS is associated with a variety of intestinal and systemic symptoms. Amylase-trypsin inhibitors from gluten activate innate immunity and increase pro-inflammatory cytokines in the intestines. Incomplete gliadin digestion increases intestinal permeability and can result in the release of pro-inflammatory excess bacterial lipopolysaccharide into circulation. While the gluten/gliadin association is strong, the culprit protein in this condition has yet to be identified with certainty. NCGS symptoms can include:

Different tests can be used to differentiate between the three conditions. Let’s take a look at the different types of testing and what they tell us.

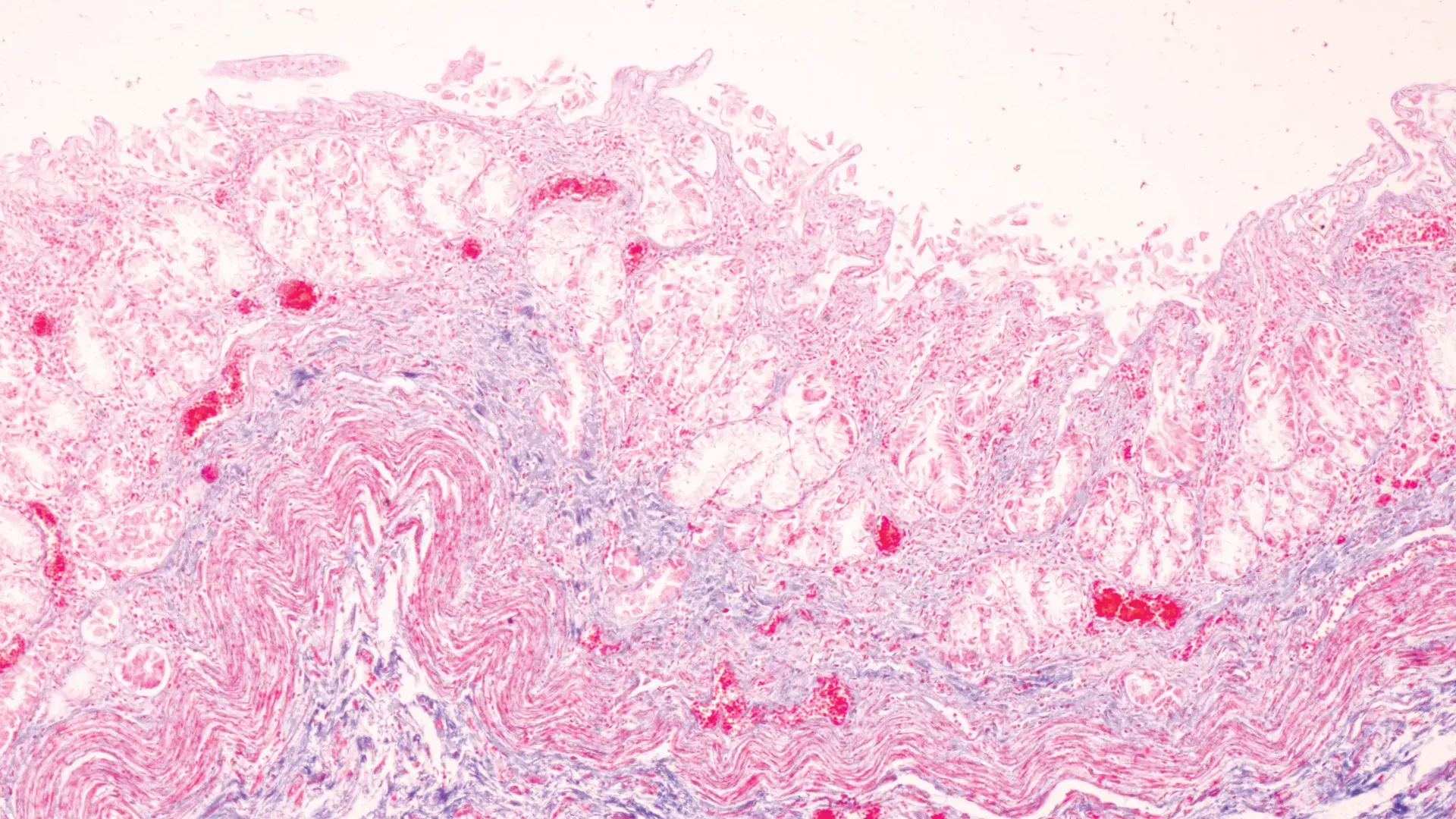

The gold standard for Celiac diagnosis is a positive duodenal biopsy and positive serological testing. Due to the invasive nature of the biopsy, many clinicians choose to evaluate serology first and treat if the serology is positive:

The problem for Celiacs is not the gluten, but the protein gliadin released during digestion which raises zonulin levels and causes tissue damage to the small intestine. US BioTek’s serum Celiac Panel measures damage marker tissue transglutaminase (tTG) IgA & IgG, in addition to IgA and IgG antibodies specific for deamidated gliadin peptide (DGP), which can help to assess the condition.

The caveat for Celiac serology is that the results will be negative if there has not been a recent gluten/gliadin exposure. Post-exposure it can take 3-4 weeks for Ig levels to build up so that an accurate assessment can take place, and levels can fall dramatically after 6-12 months of total gluten abstinence. It can be difficult for clinicians to coax gluten-free patients back onto a gluten diet so that a proper assessment can be done. Fortunately, a protocol has been developed to minimize the ill effects of gluten exposure while building adequate antibody levels:

For patients who refuse to allow even small amounts of gluten/gliadin back into their diets, alternative testing, such as HLA genetics may be pursued instead.

The development of IgE food allergy and non-IgE-mediated (IgG) food sensitivity is complex. For IgE type I hypersensitivity reactions, there must be an initial “priming” exposure to the antigen which results in an IgE reaction upon additional exposure. The initial event often occurs during an unrelated immune response (skin injury, antigen inhalation, gastrointestinal disorder or pathogen, microbiome disruption). Once the immune system creates an IgE response, memory B-cells are formed to perpetuate the allergy. In addition, some individuals may have a genetic predisposition to wheat allergy which can result in autoimmune eosinophilic esophagitis or eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Human trials indicate that for eosinophilic GI disorders, IgG4 testing is the most accurate for detecting wheat and other trigger foods.

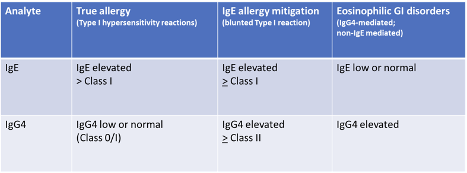

Serum IgE testing is used to identify a true food allergy. Ideally, IgG4 and IgE are evaluated simultaneously because there are specific disease-related patterns:

While there are no validate NCGS biomarkers yet increased IgG against gliadin has been associated with NCGS, particularly when combined with a negative Celiac panel. Like Celiac testing, recent gluten exposure is essential for the proper identification of NCGS patients. From a clinical perspective, any patient with NCGS symptoms and elevated gluten/gliadin antibodies should be screened for Celiac disease and then considered for a gluten-free diet therapeutic trial, as gliadin IgG will decline in over 90% of NCGS patients after six months of stringent gluten avoidance.

The treatment of all gluten/gliadin-related disorders begins with gluten abstinence. Wheat, gluten, and gliadin may be hidden components in a variety of foods, for a comprehensive list of potential sources see US BioTek’s November 2020 blog on Hidden Food Sources https://www.usbiotek.com/blog/hidden-foods-and-chronic-symptoms .

Treatment then varies based upon the ultimate diagnosis. IgE allergy may be manageable with desensitization therapies. Celiac disease requires stringent, life-long gluten avoidance. NCGS may or may not be a “forever” condition, and once contributing factors such as leaky gut, digestive disorders, or microbiome disruptions have been managed and gut homeostasis restored, it may be possible for these individuals to tolerate occasional small exposures with a minimal negative effect.

The selection of appropriate treatment strategies varies by the type of gluten/gliadin reaction and requires an accurate diagnosis of wheat, gluten, and gliadin-sensitive conditions. Accurate diagnosis requires screening for IgE, IgG4, IgG, and Celiac biomarkers.

Join us on June 22nd, 2021 for a webinar as we explore gluten and gliadin reactions as well as why wheat is such a notorious culprit. In addition, we'll review the documentation tolerance to non-Gluten grains (for safe substitutes).

Barbaro MR, Cremon C, Stanghellini V, Barbara G. Recent advances in understanding non-celiac gluten sensitivity. F1000Res. 2018 Oct 11;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1631.

Bellinghausen I, Weigmann B, Zevallos V, Maxeiner J, Reißig S, Waisman A, Schuppan D, Saloga J. Wheat amylase-trypsin inhibitors exacerbate intestinal and airway allergic immune responses in humanized mice. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019 Jan;143(1):201-212.e4.

Caio G, Volta U, Tovoli F, De Giorgio R. Effect of gluten free diet on immune response to gliadin in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Gastroenterol. 2014 Feb 13;14:26.

Caio G, Volta U, Sapone A, Leffler DA, De Giorgio R, Catassi C, Fasano A. Celiac disease: a comprehensive current review. BMC Med. 2019 Jul 23;17(1):142.

Caminero, A., et al. (2015). Differences in gluten metabolism among healthy volunteers, coeliac disease patients and first-degree relatives. British Journal of Nutrition, 114(8), 1157-1167.

Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, Bouma G, Carroccio A, Castillejo G, Cellier C, Cristofori F, de Magistris L, et al. Diagnosis of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity (NCGS): The Salerno Experts' Criteria. Nutrients. 2015 Jun 18;7(6):4966-77.

Cianferoni A. Wheat allergy: diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2016 Jan 29;9:13-25.

Infantino M, Meacci F, Grossi V, Macchia D, Manfredi M. Anti-gliadin antibodies in non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2017 Mar;63(1):1-4.

James LK, Till SJ. Potential Mechanisms for IgG4 Inhibition of Immediate Hypersensitivity Reactions. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2016 Mar;16(3):23.

Leffler D, Schuppan D, Pallav K, Najarian R, Goldsmith JD, Hansen J, Kabbani T, Dennis M, Kelly CP. Kinetics of the histological, serological and symptomatic responses to gluten challenge in adults with coeliac disease. Gut. 2013 Jul;62(7):996-1004.

Loffredo L, Ettorre E, Zicari AM, Inghilleri M, Nocella C, Perri L, Spalice A, Fossati C, De Lucia MC, Pigozzi F, Cacciafesta M, Violi F, Carnevale R; Neurodegenerative Disease study group. Oxidative Stress and Gut-Derived Lipopolysaccharides in Neurodegenerative Disease: Role of NOX2. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020 Jan 31;2020:8630275.

Novak N, Bieber T, Peng WM. The immunoglobulin E-Toll-like receptor network. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151(1):1-7.

Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, Frati F. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008 Sep;153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-6.

Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, Calderwood AH, Murray JA; American College of Gastroenterology. ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108(5):656-76; quiz 677.

Vighi G, Marcucci F, Sensi L, Di Cara G, Frati F. Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008 Sep;153 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):3-6.

Wright BL, Kulis M, Guo R, Orgel KA, Wolf WA, Burks AW, Vickery BP, Dellon ES. Food-specific IgG4 is associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Oct;138(4):1190-1192.e3.

Unlocking the Secrets of Cellular Energy

Short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) are organic acids produced by bacterial fermentation of dietary fibre and resistant starch. Enterocytes and...

Zonulin has emerged as a popular marker to assess the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Discovered by Dr Alessio Fasano, Zonulin...